Home

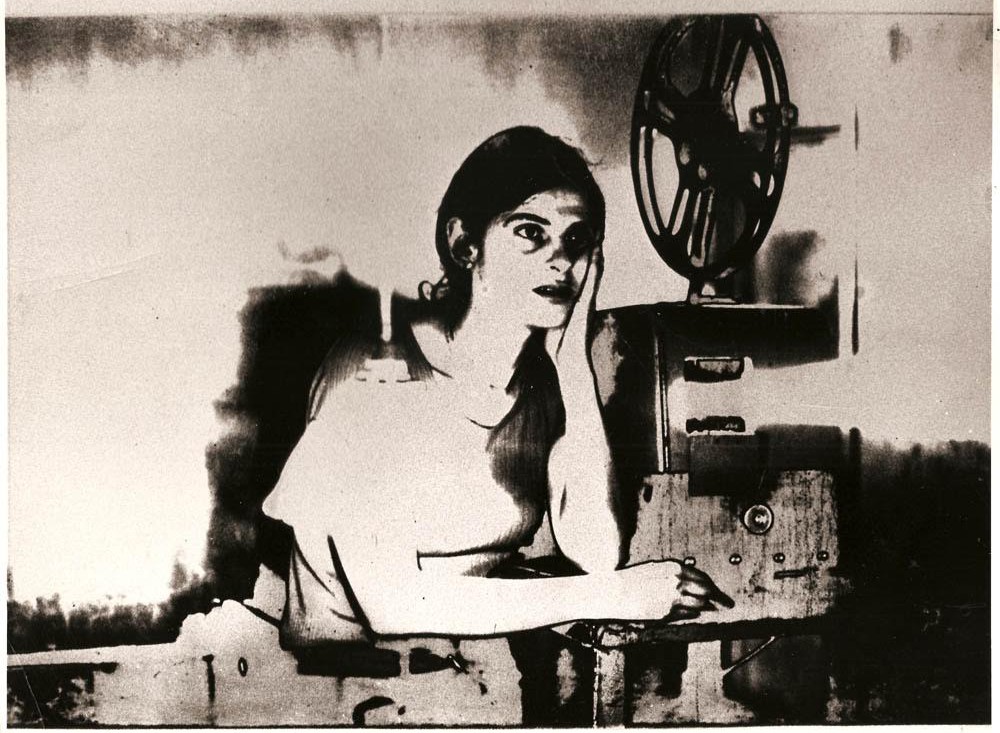

“What is She looking at? What Does She See?”

Artist/Activist Activist/Artist (a personal story)

“Art is not a mirror held up to reality but a hammer with which to shape it.”

-Bertolt Brecht

One advantage of having had the good fortune to live into old age is that I can look back and see my life in art and activism as a story, a journey that begins with three facts about myself as a child: I was aware in some way of being in opposition to the society I grew up in; I was keenly interested in what was happening in the world; and I knew that what happened in the world had, in some way, an impact on my small life.

This longevity, (for which I am grateful!), offers me the opportunity to reflect on personal intentionality and processes of engagement against a changing social and political backdrop. Art and Activism. Although there have been many permutations and combinations in how I managed these activities, I can’t really separate my journey into political radicalization from my development as an artist, nor can I separate my activist intervening in struggles for social justice from the creative work I’ve done. They coincide. The same path, the same journey of learning, of opening. A journey conducted within specific social cultures of resistance to repression in the political conditions of specific times.

In the early 1970’s, for the first time I made art that I was satisfied enough to consider myself an artist. I very much followed the pattern of what artists do – work, apply for grants, apply for shows, try to sell work. And although my work had feminist themes, it would be an exaggeration to characterize it as ‘political art’, engaged in the arena of struggles for equality. I was at the time a member of the first women’s artist run centre in Canada, Powerhouse, (which later became La Centrale) and I participated in women’s consciousness raising groups. Women’s Liberation was in the air, but it was a middleclass, white movement in my experience. Similarly, although we demonstrated against the Vietnam War and some of us helped War Resistors coming from the US, I see these kinds of actions now as being reactions to events without a deeper analysis of historical imperialism, neo-imperialism, capitalism and racism, without the development of strategies for bringing about systemic change that we see so widespread today. Different times!

It was in the early 1980’s that I first made a conscious decision to do explicitly political art. A genocidal slaughter of the Mayan people was occurring in Guatemala, one that had been going on for many years but was particularly brutal at that time. I had become more active politically and my understanding of the systemic roots of injustice, colonialism, and militarism had grown. I was part of a support group, mainly composed of Guatemalan refugees. Very few Canadians knew what was happening and I wanted to do what I could to inform them. By bringing my art practice and my activism together in concrete ways, by situating what I created into the realm of the political, I could, I felt, reach out to a participatory audience, and a wider range of viewers who would not ordinarily come to an art gallery.

“Guatemala: The Road of War”, a multi media installation was the result. It was exhibited in 12 Artist Run Centers across Canada, and in New York City, accompanied in each town or city by programs of speakers, benefit concerts, films, activist initiatives, and created with the cooperation and support of local human rights groups, church groups, social activist organizations, and solidarity groups, in order to enlarge the scope of participation and attendance far beyond the gallery walls. In every city and town, in addition to programs of events, I was interviewed on radio, and articles and revues were written. In this way, the media served to spread the word about the issues involved and Canada’s relationship to them.

I did extensive research for the Guatemala installation which led me to a deeper understanding of Israel’s role in the suppression of people’s struggles for justice in the world, thus marking a beginning of my involvement and support of the Palestinian cause. I was not a Zionist before then but knew comparatively little, so it was very enlightening to learn that Israel not only supplied successive Guatemalan governments with weapons, they also provided intelligence and operational training to Guatemalan military officers, and technical support to counterinsurgency agencies.

One of the questions that raged in the art world at the time that I did the Guatemala show was the issue of white artists’ cultural appropriation of others and I was criticized by some for speaking in the name of Guatemalans. I realized that as a political activist I had a different perspective – after all, how could Canadians know or care about what was happening in Guatemala unless they somehow learned about it? And how does one understand or build solidarity? However, it did cause me to think more about whether people could relate to and empathize with Guatemalan Indians in a way that was hopefully not patronizing and colonialist. The Guatemalans in their beautiful clothing could so easily be exotified and made the ‘Other”. While some people might be sympathetic and horrified, at the same time they might feel that the plight of the Mayans was happening far away and had nothing to do with their lives, which of course was not true.

With these thoughts, I began another large installation, “The Global Menu” an exposition of the very concrete relationship between us, the people of the First World, us, and those in what we then called the Third World, countries decimated and impoverished by colonization and exploitation. The answer was food, its globalized production patterns and distribution (at that time). Who produces our food and at what cost to them? Who feeds whom? Again the exhibition was conceived of as part of a larger project that would include organizations and individuals whose concerns converged in the many issues involved in the global system of food production and distribution. I went to the Philippines to do research as it was an example at that time of a lush, green land being used for export monocrops while its people were starving. Basically the work was composed of contrasting sites – our world and the so called developing world: a supermarket and Chile after the coup; a Canadian dining room and an unemployed Filipino sugar workers family shack. The work also exposed conditions of exorbitantly high food costs, poverty and malnutrition amongst First Nation communities in Canada, our Third World, which are now worse than ever.

The following is an excerpt from a revue of “The Global Menu” by Salah Dean Hassan and published in Fuse Magazine in 1990. It very neatly describes my process:

“The process of developing and successfully executing projects that create links between community-based groups is at the core of Guttman’s art. The organizations that mobilized their support behind ‘The Global Menu’ identify with the project; they see themselves as – and indeed are – part of it. Similarly, Guttman inscribes her exhibition within the field of ongoing struggles. In many ways, it is necessary to view the exhibition and the corresponding events (in Montreal, a weekly film series at the NFB, video screening at Cinema Parallele, a slide show on the Philippines, a benefit concert, a benefit dinner, a tour of supermarkets and lectures) as elements which constitute a whole. One event supports the other, touching different milieus and individuals so that the impact of the project extends beyond the relatively insular context of an artist-run gallery.”

In 2000 the second Intifada began and large numbers of people in sympathy with the Palestinian cause around the world roused themselves to finally become actively involved in that struggle. Tadamon was established in 2005 and I became an active member and have been until recently. I also went to Palestine 4 times and in those years I created works – “tourist postcards”, posters aand others – about Palestine that are still used in campaigns to inform and recruit people to become active in the Palestinian struggle. A little later I began, like many others to be an active supporter in a myriad of mobilizations of the many activist organizations in Montreal, not always as a member but in solidarity, participating in making banners, in demonstrations and actions. Montreal had by then become a hub of Anarchist activity, much to my grateful delight. Since then I feel like I am home, where I’ve always wanted to be, in a community that I have always wanted to be a part of.

From 1995 – 2005, I worked intensely on a deeply personal project, Notes From the 20th, a continuum of 4 multi-media installations. It was meant be a look backward at the violent 20th century, one in which I will have lived most of my life. As well, it was meant to be the last time I would participate as an artist in the ‘Art World” in any conventional sense. During this period of my life, I divided my time between doing my artwork and organizing exhibits for it, and separately, being extremely active here, as I’ve described above, and in Palestine.

The first installation work was an exploration of the ways in which my small life has been determined by the contingencies of my birth – the time, and place, my gender, class, my family’s patriarchal structure, the fact that I am Jewish – as well as by the historical forces which were a background to my childhood. I was attempting to reconstruct both personal and historical memory, and how they are woven together. As well it dealt with the relationship of patriarchy to fascism. As the project progressed, I was drawn more and more to the life and work of Walter Benjamin, considered by many to be one of the great thinkers of the 20th century. The subsequent three installations were about his life and his ideas. His view of history as one unending catastrophe that necessitates an awakening on our part, seemed especially important to me as the 21st century began. Benjamin rejected the notion of history as progress, and prophesized that as long as we refuse to learn from the past, we will live in endless cycles of war and violence. Notes From the 20th was exhibited in Canada several times between 1998 and 2007.

In 1990 I was interviewed in an art magazine, Harbour, about “The Global Menu” and I was asked how I saw the future development of political art. At the time, I felt very much alone as an artist, dealing with political issues and trying to place my work within an activist framework. I said that I hoped that in the future there would be a large community of activist artists that I could be a part of. My wish has come true. Now as never before there is a richly textured resistance culture, which anyone can be part of without having to call themselves artists or feel that they need special training or permission to do art. The notion that everyone is an artist is deeply embedded in principles of Anarchy. In the beautiful utopian world that Anarchist movements wish to bring about, everyone will be free to realize a fulfilled life, to be creative, to express themselves. Everyone will be free of wage slavery, free of educational systems that imprison the mind and soul, free of the violence of Capitalism.

I have lived many changes in perceptions of what art is and for whom, how is it can be commodified and how it can be used as a powerful tool of social mobilization for justice. Art is now posters, graffiti, street art, knitting, installations and performances in public places, taking over a space and any creative endeavor that one can think of. I have lived through different patterns of collective involvement in struggles until today when there are so many more activists-artists involved in present struggles, who are part of the larger community of activists and who see all struggles in the world connected, part of a global pattern. And who seize opportunities for ‘doing’ in the grass roots sense: on our own, drawing on our talents, our allies, our intense involvements in the struggles of our times – locally and globally, our awesome energies, our grass roots know-how, our communities and our strong sense of solidarity. We are much better equipped to speak truth to power and reach others than ever. And are needed more than ever. Art is needed more than ever now.

Freda Guttman